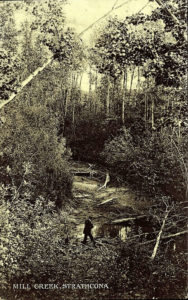

“The Mill Creek Ravine is one of the most changed places in the city. It has been through so many transformations.”

Jan Olson knows of what she speaks. She is an anthropologist and archeologist who describes the ravine’s extensive and colourful history in her book “Scona Lives.”

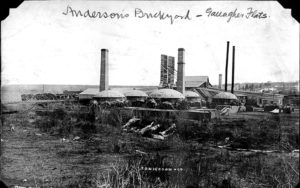

“Paleo-Indigenous peoples, Cree, Blackfoot, Papaschase, European settlers and modern residents have all used the Mill Creek Ravine,” she writes. “The ravine has been an area for nature to thrive and hunting to occur; a location for spiritual rituals; a place for industrial plants (meat packers, brick makers, dumps); an area for adventure; and an area for recreation.”

As long as people have been in what is now Edmonton, the Mill Creek Ravine has been part of their lives. Of course, the ravine wasn’t always named Mill Creek. The Cree aptly called it Stony Creek. European settlers came to call it Mill Creek—from a short-lived flour mill that was operating on the creek’s banks in the 1870s.

Over the decades, the ravine has been a corridor for transportation. Some of it was pretty intrusive: part of the Edmonton, Yukon and Pacific Railway line went through it, carrying passengers and serving industries in the ravine: a brickyard, a coal mine and two meat packing plants. Most of the line was abandoned in 1954, but a spur line serving Gainers (a meatpacking company) remained in use until 1980. Vestiges of the railway can be seen in the ravine today in the form of four wooden trestle bridges that are part of a multi-use trail.

Olson says all that ill treatment of the ravine lasted right into the 1970s.

“It was very dirty. It was very messy. All that stuff went right into the creek,” she says. “I interviewed people who were telling stories of how disgusting the ravine was in the 1940s. Parents wouldn’t want their kids to go down there because of how much garbage there was. It was a toxic wasteland really.”

The demise of the rail line did not mean the end of attempts to use Mill Creek Ravine as a major commuter route.

In the 1960s, the City of Edmonton wanted to put a freeway through it to connect downtown with the south side. Opposition to the freeway was swift and passionate. Hundreds of angry residents packed community meetings and signed petitions. Finally, in May of 1971, city council agreed with those fighting the freeway, and rejected the plan.

But the battles were not entirely over.

With the freeway off the table, the City then wanted to turn the ravine into a highly developed park, with a theatre, museum, day camps and the like. The old Gainers plant would have been turned into a youth hostel. “They were going to have tennis courts and volleyball centres and skating ponds,” Olson says. “They were going to take out 400 houses north of Whyte Avenue surrounding the creek.”

Once again residents and community groups rose in opposition and eventually the City agreed to leave things alone. The ravine was the park. Something Olson calls an oasis of refuge.

“Today in the winter, the ravine is used for bird watching, skiing, walking, cultural festivals, tobogganing and snow forts,” she writes. “In the summer, there are many dog walkers, off road bikers, commuters on bike and foot, festivals, runners, baseball, hide and seek, tag, adventure play, community and individual picnics, sitting benches, the Mill Creek pool, weddings and a place where neighbours run into each other.”

“This continual use of the ravine for over centuries makes it a special location,” Olson continues. “It also has spiritual overtones as people have seen the northern light at night in wintertime, or felt the warmth of a fire at the Flying Canoë Volant Winter Festival; some feel transported to another place. The light through the trees can help one through mourning, or to experience peace with a gentle sun on their face.”

Related Stories

Muttart

Centuries of change flow through Mill Creek Ravine

Cloverdale: From industrial area to verdant neighbourhood