Scrip was introduced in Canada more than 150 years ago, and the scars remain to this day.

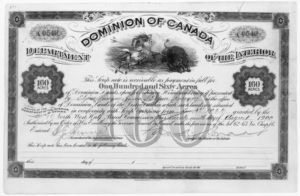

This description of scrip can be found in the Canadian Encyclopedia: “Scrip is any document used in place of legal tender, for example, a certificate or voucher, where the bearer is entitled to certain rights. In 1870, the Canadian government devised a system of scrip that issued documents redeemable for land or money. Scrip was given to Métis people living in the West in exchange for their land rights.”

There were two types of scrip. Money scrip was issued for $20, $80, $160 and $240. Land scrip was issued in allotments of 80, 160 and 240 acres. Whether we are talking money or land, scrip was basically an easy and cheap way for the federal government to acquire land in the west for White settlement and commercial development.

Just ask Krista Leddy. She is a lifelong Edmonton resident whose Métis family has lived in the area for generations. Leddy says the history of scrip is a dark one:

“You look at the story around river lots and for Métis people… there were people that were literally chased off the land—off their land. And so, while Métis were really important in helping build this place, Edmonton, even the highways, the roads, the major roads were based on Red River cart trails… We kind of got pushed aside.”

Leddy adds, “For a long time, it wasn’t safe to be openly Métis. We’re fortunate we come from a family that had economic and political power because of who they are in St. Albert and Lac Ste. Anne so that identity was kept. But that’s not true for a lot of Métis people.”

Unlike with First Nations peoples who negotiated numbered treaties as bands, the federal government dealt with the Métis on an individual basis. As a result, the scrip system led to conflicting perspectives between Métis people and Ottawa over rights to traditional lands.

The Canadian Encyclopedia says the scrip process was also legally complex and disorganized. This made it difficult for Métis people to acquire land, and it simultaneously created room for fraud. Leddy says Métis people usually couldn’t even claim land where they were and had to go elsewhere. The process was also incredibly slow.

“And then you had to claim it, and then that would get sent to Ottawa and then come back and it could be years before you finally got the certificate that said, okay… you have a right to that land, but then there was still a thing needed to get the deed,” Leddy says. “It was a very complicated process. Not all Métis people quite understood the process, so they may have gone to where they were assigning scrip, and then someone outside is like, here’s some money, I’ll take that from you and not understand that value. They often used some of our poverty against us as a way to cheat us out of what was ours… Yeah, it’s a complicated, dark part of history.”

In the last 50 years, the Métis Nation has been involved in treaties where Métis people agreed to surrender their claims to scrip for treaty rights.

In 1981, the Manitoba Métis Federation took the federal government to court, arguing that the Métis did not receive the lands they were promised in the Manitoba Act of 1870. They said the scrip system failed to provide the Métis the homesteads they were guaranteed. After decades of legal battles, the case ended up in the Supreme Court, and in 2013 it ruled the federal government indeed failed to distribute lands to the Métis in accordance with “the honour of the Crown.”

Three years later, the Manitoba Métis Federation and Ottawa signed a framework agreement to address issues brought forward in the case. In 2017, the federal government signed another framework agreement with the Métis Nation of Alberta to allow for the negotiation of Métis rights to self-government. The president of the Métis Nation of Alberta said the framework “establishes a process to acknowledge the sorry legacy of Métis scrip.”

Related Stories

Tawatinâ Bridge

“The Sorry Legacy of Métis Scrip”

Alberta’s Famous Five and Edmonton’s parks that bear their names