“We’ve always looked for the opportunity to keep history alive through reclaiming wood. It’s our business, but it’s also our passion. I absolutely love history.”

Darren Cunningham, the co-founder of Urban Timber, got the chance to keep history alive after the City of Edmonton dismantled the Cloverdale footbridge in 2016 to make way for the new Tawatinâ LRT and pedestrian bridge.

“I just love to see how this city evolves,” he says. “It’s exciting at times, and it’s heartbreaking at other times. And certainly with the Cloverdale bridge, it was one of those heartbreaking moments.”

Cunningham became involved when the City of Edmonton contacted him, asking if Urban Timber could take the wood from the dismantled bridge off its hands. The catch was that the company had to take all of it… And there was a lot. Cunningham estimates about 4,000 linear feet, made up of 16-foot fir, spruce and pine planks.

For four decades, the Cloverdale footbridge had held a special place in the hearts of people, especially residents of Cloverdale and Riverdale. Many memories were engraved into the bridge itself, and some users were very upset about its removal. Something Cunningham soon found out.

“I don’t want to say it was aggressive. It was just passionate,” he says. “I really loved the passion out of both communities. I’ve joked about how if I want to take anyone to a street fight, I’m taking those two communities with me. They were so passionate about this bridge and they just wanted to make sure the wood was going to good use, what was happening with it. Who had access to it was probably the biggest question.”

“So I opened it up and I said Riverdale and Cloverdale… you guys get first access to it,” Cunningham continues. “Let’s let the communities buy the wood back, however they want to buy it. A lot of the wood I just donated back to the community… like if someone just wanted a piece of wood for their backyard to make into a swing set… I just gave them that wood.”

Cunningham even donated wood from the bridge to a restaurant in Riverdale to build a deck. But first, there was a lot of work to do to get the wood ready to build things. “What most people don’t realize is that there was a pretty hefty expense on our end to get that wood out of the yards where it was resting and into our yard,” Cunningham says. “And then once we got it, it was full of eight inch spindle nails. We had to pull every single nail out of every single board before we could run any of it through our machinery.”

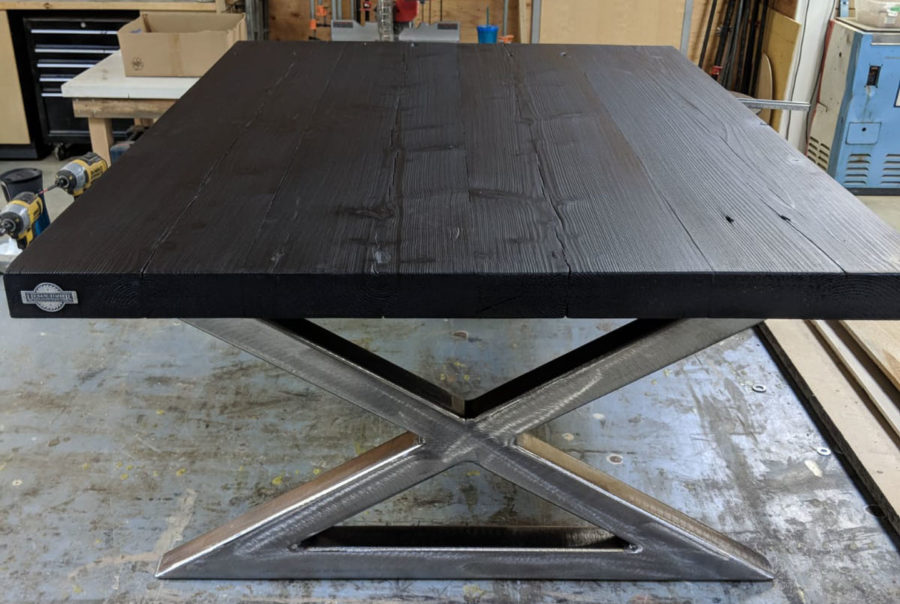

There were also concerns about the environmental safety of the coating on the wood. But testing revealed the coating on the planks to be used for furniture could be skinned off. The ten artisans at Urban Timber ended up mostly building coffee tables and dining room tables from the bridge wood. Almost all were bought by people in Cloverdale and Riverdale. “What was cool was we did little plaques on every piece of furniture,” Cunningham says. “So all of the tables had plaques that said ‘This table was constructed using wood out of the Cloverdale footbridge.’ When you start selling history… People got married on that bridge. We sold at least three tables to couples who got married on the bridge… pretty cool.”

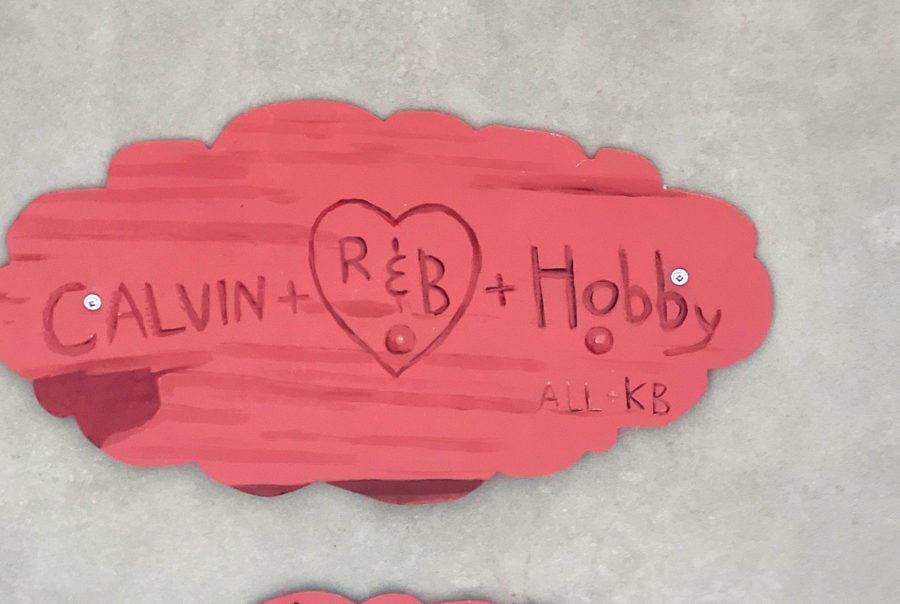

Another way the old footbridge lives on is through the art on the new Tawatinâ Bridge. Metis artist David Garneau is the great, great grandson of Laurent Garneau, for whom the southside neighbourhood of Garneau is named. He led a team of a dozen artists that created more than 540 paintings that now adorn the Tawatinâ Bridge. Garneau knew it was important for the art in the new bridge to memorialize the old one. “Community people were fairly upset about this big change and the loss, and I really took it to heart and wondered what I could do to commemorate that old bridge,” he says.

“You might not notice them right away but there are some small things. One image of the bridge from a satellite seen from above, on one small panel there’s a very large image of ice floes and you can see the shadow of the bridge.”

But the big thing was painting many of the messages that people had carved into the old railings. Messages of love or memorials. Those messages are captured in forty paintings at the south entrance to the new bridge.

Garneau has been moved by people’s reactions: “I heard back from so many people who are walking that bridge every day and were telling me how much they appreciated that touch, that memorialization was not lost. And other people who were able to track down their own carvings, or their relatives’ carvings. That really meant a lot to me.”

Related Stories

Tawatinâ Bridge

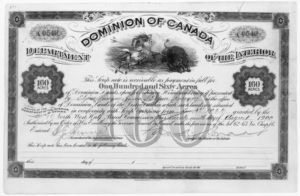

“The Sorry Legacy of Métis Scrip”

Alberta’s Famous Five and Edmonton’s parks that bear their names